I went onto the BBC website as I feel it is a reliable source:

"Buddhism is a spiritual tradition that focuses on personal spiritual development and the attainment of a deep insight into the true nature of life. There are 376 million followers worldwide.

Buddhists seek to reach a state of nirvana, following the path of the Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama, who went on a quest for Enlightenment around the sixth century BC.

There is no belief in a personal god. Buddhists believe that nothing is fixed or permanent and that change is always possible. The path to Enlightenment is through the practice and development of morality, meditation and wisdom.

Buddhists believe that life is both endless and subject to impermanence, suffering and uncertainty. These states are called the tilakhana, or the three signs of existence. Existence is endless because individuals are reincarnated over and over again, experiencing suffering throughout many lives.

It is impermanent because no state, good or bad, lasts forever. Our mistaken belief that things can last is a chief cause of suffering."

"The Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha, was born into a royal family in present-day Nepal over 2500 years ago. He lived a life of privilege and luxury until one day he left the royal enclosure and encountered for the first time, an old man, a sick man, and a corpse. Disturbed by this he became a monk before adopting the harsh poverty of Indian asceticism. Neither path satisfied him and he decided to pursue the ‘Middle Way’ - a life without luxury but also without poverty.

Buddhists believe that one day, seated beneath the Bodhi tree (the tree of awakening), Siddhartha became deeply absorbed in meditation and reflected on his experience of life until he became enlightened.

By finding the path to enlightenment, Siddhartha was led from the pain of suffering and rebirth towards the path of enlightenment and became known as the Buddha or 'awakened one'."

Visual Research about the Buddha:

http://home.swipnet.se/gostaratna/Buddha17.jpg

http://blog.tsemtulku.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/06/buddha.jpg

http://thecostaricanews.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/The-Buddha.jpg

http://www.bubsoc.org/wp-content/uploads/2009/11/gautama-buddha.jpg

http://bhikkhucintita.files.wordpress.com/2012/02/buddha.gif

http://www.craftsinindia.com/newcraftsimages/BRASS0013PL.jpg

http://www.kalsangdawa.com/gallery/medicinebuddhaazure.jpg

http://www.chinapictures.org/images/yunnan/1/yunnan-40116100646656.jpg

http://us.123rf.com/400wm/400/400/kobchaima/kobchaima1105/kobchaima110500060/9665201-chinese-buddha-statue-at-the-thai-temple-thailand.jpg

There are slight differentiations in the appearance of the Buddha according to the cultural and geographical interpretations of Buddhism ie Thai, Chinese, Japanese, & Indian Buddhism all visualise the Buddha in a different way. For example: Chinese Buddhism tend to portray him slightly fatter than other portrayals.

"Key facts

- Buddhism is 2,500 years old

- There are currently 376 million followers worldwide

- There are over 150,000 Buddhists in Britain

- Buddhism arose as a result of Siddhartha Gautama's quest for Enlightenment in around the 6th Century BC

- There is no belief in a personal God. It is not centred on the relationship between humanity and God

- Buddhists believe that nothing is fixed or permanent - change is always possible

- The two main Buddhist sects are Theravada Buddhism andMahayana Buddhism, but there are many more

- Buddhists can worship both at home or at a temple

- The path to Enlightenment is through the practice and development of morality, meditation and wisdom."

"The Four Noble Truths

Statue of Buddha, 1st-2nd century CE, Afghanistan ©

Statue of Buddha, 1st-2nd century CE, Afghanistan ©

"I teach suffering, its origin, cessation and path. That's all I teach", declared the Buddha 2500 years ago.

The Four Noble Truths contain the essence of the Buddha's teachings. It was these four principles that the Buddha came to understand during his meditation under the bodhi tree.

- The truth of suffering (Dukkha)

- The truth of the origin of suffering (Samudāya)

- The truth of the cessation of suffering (Nirodha)

- The truth of the path to the cessation of suffering (Magga)"

What I have come to learn from this passage

The first Noble truth - the truth of suffering

From reading further into the 4 noble truths on this page, I have come to understand that Buddhists believe that the root of suffering, (other than the obvious causes of old age, sickness and death), starts with the fact that human beings are subject to desires and cravings. Meaning that because life fails to live up to our expectations, we are not satisfied and unfulfilled. Once we have come to understand the truth of suffering, we can learn how to cope with suffering by changing our outlook on life in a non-pessimistic, but realistic way.

The second Noble Truth - Desire is the root of evil - Tanhā

The Buddha teaches the origin of suffering through the 3 roots of evil/ the 3 fires/ the 3 poisons. These are greed/ desire, ignorance/ delusion, hatred/ destructive urges. All are represented visually in art through animals. Greed being a rooster, Ignorance being a pig and hatred being a snake.

"Language note: Tanhā is a term in Pali, the language of the Buddhist scriptures, that specifically means craving or misplaced desire. Buddhists recognise that there can be positive desires, such as desire for enlightenment and good wishes for others. A neutral term for such desires is chanda.""The Fire Sermon

The Buddha taught more about suffering in the Fire Sermon, delivered to a thousand bhikkus (Buddhist monks).

Bhikkhus, all is burning. And what is the all that is burning?The eye is burning, forms are burning, eye-consciousness is burning, eye-contact is burning, also whatever is felt as pleasant or painful or neither-painful-nor-pleasant that arises with eye-contact for its indispensable condition, that too is burning. Burning with what? Burning with the fire of lust, with the fire of hate, with the fire of delusion. I say it is burning with birth, aging and death, with sorrows, with lamentations, with pains, with griefs, with despairs.The Fire Sermon (SN 35:28), translation by N̄anamoli Thera. © 1981 Buddhist Publication Society, used with permission

The Buddha went on to say the same of the other four senses, and the mind, showing that attachment to positive, negative and neutral sensations and thoughts is the cause of suffering."

The Third Noble Truth - Cessation of suffering - Nirodha

Because the Buddha taught that the root of evil and suffering comes from human beings attachment to desire, he also taught that human beings must detach themselves from feelings of desire, 'the possibility of liberation'. Buddhists know that Buddha was living proof that freedom from desire was possible during a human beings lifetime.

(taken from the BBC website)

Bhikkhus, when a noble follower who has heard (the truth) sees thus, he finds estrangement in the eye, finds estrangement in forms, finds estrangement in eye-consciousness, finds estrangement in eye-contact, and whatever is felt as pleasant or painful or neither-painful- nor-pleasant that arises with eye-contact for its indispensable condition, in that too he finds estrangement.The Fire Sermon (SN 35:28), translation by N̄anamoli Thera. © 1981 Buddhist Publication Society, used with permission

"Estrangement" here means disenchantment: a Buddhist aims to know sense conditions clearly as they are without becoming enchanted or misled by them.

By extinguishing the 3 fires of evil and by becoming liberated from desire, a Buddhist can reach a state of Nirvana.

"Someone who reaches nirvana does not immediately disappear to a heavenly realm. Nirvana is better understood as a state of mind that humans can reach. It is a state of profound spiritual joy, without negative emotions and fears.

Someone who has attained enlightenment is filled with compassion for all living things.

After death an enlightened person is liberated from the cycle of rebirth, but Buddhism gives no definite answers as to what happens next.

The Buddha discouraged his followers from asking too many questions about nirvana. He wanted them to concentrate on the task at hand, which was freeing themselves from the cycle of suffering. Asking questions is like quibbling with the doctor who is trying to save your life."

The fourth Noble Truth - The Path to the Cessation of Suffering

Buddha teaches how to reach the state of Nirvana through the Eightfold Path, represented in art through a ships wheel with 8 spindles. The Eightfold Path can also be referred to as the Middle way, a way of living not in poverty nor luxury.

Eight principles of the Middle Way:

1. Right understanding - Sammā ditthi

2. Right intention - Sammā san̄kappa

3. Right Speech - Sammā vācā

4. Right Action - Sammā kammanta

5. Right Livelihood - Sammā ājīva

6. Right Effort - Sammā vāyāma

7. Right Mindfulness - Sammā sati

8. Right Concentration - Sammā samādhi

These 8 principles are not to be taken in stages, but to all be made aware of at one time. They outline the key states of being that are heartly required to reach the state of Nirvana.

"The eight stages can be grouped into Wisdom (right understanding and intention), Ethical Conduct (right speech, action and livelihood) and Meditation (right effort, mindfulness and concentration).

The Buddha described the Eightfold Path as a means to enlightenment, like a raft for crossing a river. Once one has reached the opposite shore, one no longer needs the raft and can leave it behind."

The four Noble truths are just the main essence of Buddha's teachings. With this in mind, I decided to visit as many Buddhists centres as possible, starting with a local Buddhist Centre in Northwich, Cheshire.

I didn't know what to expect at first. From my quick internet searches I rather stereotypically imagined a grand temple inhabited my monks but I got a real insight into modern Buddhism when discovering it was a converted house like my own. It was really interesting to see how such a radical, multi-cultural religion has been interpreted for an english society and landscape:

The leader of this Buddhist centre was absent, and so the man present there was unable to tell me much about the centre but kindly gave me a leaflet and told me to arrange a time to see the leader.

I wanted to explore some more centres, but decided to visit ones in an inner city, with the impression that these may be busier or more like what I had imagined.

I searched the internet for Buddhist centres in Liverpool as I felt that inner city centres might be bigger because of a possibly bigger audience. Here are the ones I visited:

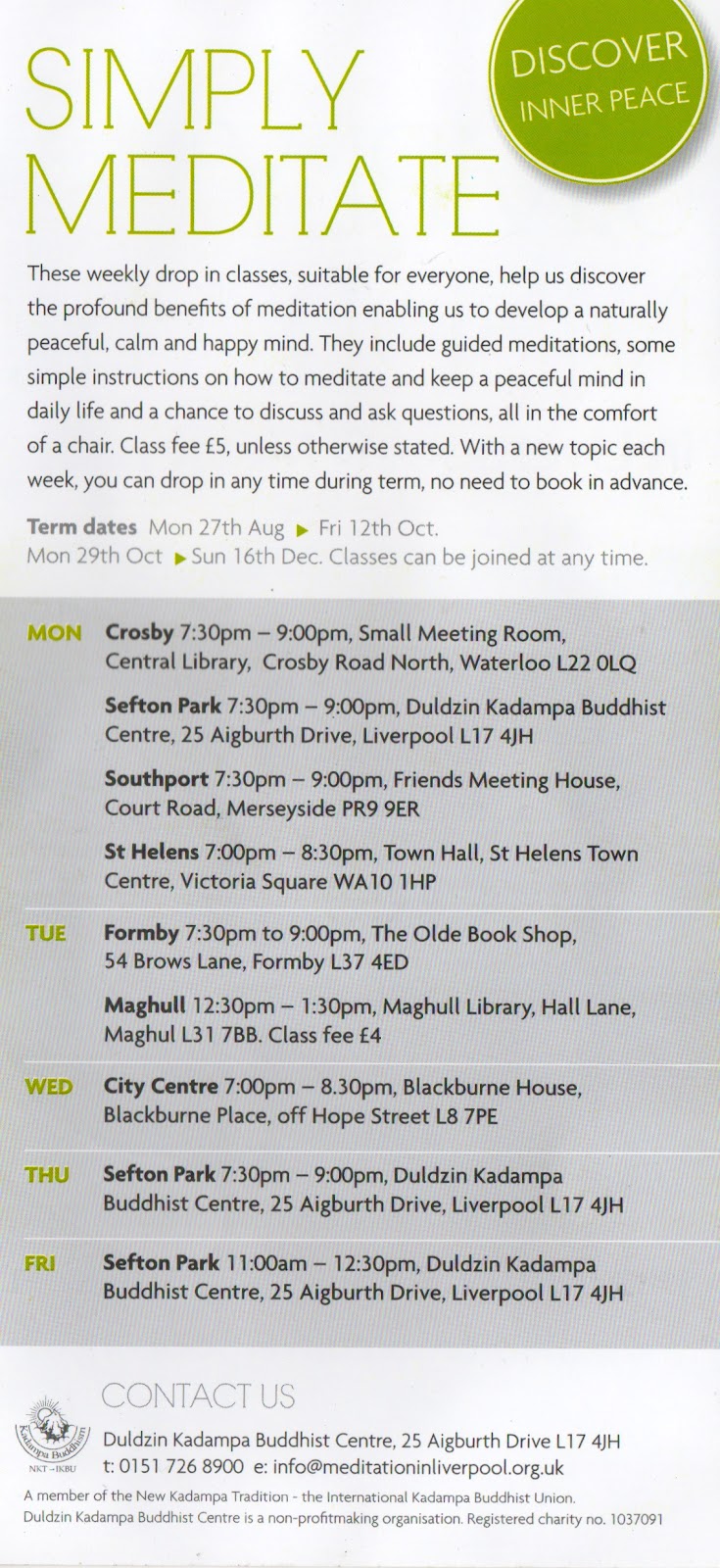

- Duldzin Kadampa Buddhist Centre, 25 Aigburth Drive, Liverpool, L17 4JH

- Diamond Way Buddhism Liverpool, 61 Newsham Drive, Liverpool

- Kagyu Shedup Ling Buddhist Group, The Old Police Station, 80 Lark Lane, Aigburth, Liverpool, L17 8UU

The first of these centres I decided to visit was the Duldzin Kadampa Buddhist centre in Liverpool. It's location was much more what I had expected: on the edge of peaceful Sefton Park. I rang the doorbell and a resident named Amy answered. She kindly agreed to give me a quick tour of the downstairs rooms and tell me a little about what goes on here.

The entrance hall was very welcoming and calm. There were many advertising leaflets and timetables to take away. I was asked to remove my shoes as we proceeded into the prayer room. Amy said that this was for respect and hygiene. I did not take any pictures in the prayer room because I was not sure if this would be OK and so this image was found on the Duldzin Kadampa website:

There was a large statue at the front of the Buddha in the Lotus praying position with several glasses of water in front of him. Amy briefly discussed that although they were offerings to the Buddha, he is content with what he has and that they are normally laid out for the Buddhists themselves.

Beautiful artwork adorned the walls with an image of a man in traditional ceremonial robes of whom later I learnt is Venerable Geshe Kelsang Gyatso, the founder of the New Kadampa Tradition.

There was a large statue at the front of the Buddha in the Lotus praying position with several glasses of water in front of him. Amy briefly discussed that although they were offerings to the Buddha, he is content with what he has and that they are normally laid out for the Buddhists themselves.

Beautiful artwork adorned the walls with an image of a man in traditional ceremonial robes of whom later I learnt is Venerable Geshe Kelsang Gyatso, the founder of the New Kadampa Tradition.

The Meditation Shop

- Theraveda

- Mahayana

- Tibetan

- kadampa

- ....

- source Wikipedia

I emailed a friend's relative who is a Buddhist, Jonathon Ashton, to find out about Buddhism on a personal level:

He also sent me a few videos on Buddhism:

"Now the Bodhisattva enters his mother's womb in the form of a white elephant, but here we encounter a little problem in that we are not informed at what moment he exchanges his animal form for a human one. The Chinese thought they solved this problem by showing the Bodhisattva as entering his mother's womb "mounted on an elephant" as shown in Figure 2, the Chinese painting of the same scene. One more point that attracts our attention is that at this decisive moment of conception Maya is always shown alone on her couch; her husband is always absent. This restraint can be attributed to the religious belief of the time that everything having to do with the birth of the Buddha be physically and morally pure. This preoccupation with moral purity is carried over to the second act, the birth of the Buddha."

the Chinese painting of the same scene. One more point that attracts our attention is that at this decisive moment of conception Maya is always shown alone on her couch; her husband is always absent. This restraint can be attributed to the religious belief of the time that everything having to do with the birth of the Buddha be physically and morally pure. This preoccupation with moral purity is carried over to the second act, the birth of the Buddha."

"The lotus flower represents one symbol of fortune in Buddhism. It grows in muddy water, and it is this environment that gives forth the flower’s first and most literal meaning: rising and blooming above the murk to achieve enlightenment.

The second meaning, which is related to the first is purification. It resembles the purifying of the spirit which is born into murkiness. The third meaning refers to faithfulness. Those who are working to rise above the muddy waters will need to be faithful followers."

source : "http://buddhists.org/buddhist-symbols/the-meaning-of-the-lotus-flower-in-buddhism/"

"In Buddhism it is used in mantras and dhāranis

A deeper insight into this mystic symbol reveals that it is composed of three syllables combined into one, not like a physical mixture but more like a chemical combination. Indeed in Sanskrit the vowel 'o' is constitutionally a diphthong compound of a + u; hence OM is representatively written as AUM.

Fittingly, the symbol of AUM consists of three curves (curves 1, 2, and 3), one semicircle (curve 4), and a dot.

The large lower curve 1 symbolizes the waking state (jagrat), in this state the consciousness is turned outwards through the gates of the senses. The larger size signifies that this is the most common ('majority') state of the human consciousness.

The upper curve 2 denotes the state of deep sleep (sushupti) or the unconscious state. This is a state where the sleeper desires nothing nor beholds any dream.

The middle curve 3 (which lies between deep sleep and the waking state) signifies the dream state (swapna). In this state the consciousness of the individual is turned inwards, and the dreaming self beholds an enthralling view of the world behind the lids of the eyes.

These are the three states of an individual's consciousness, and since Indian mystic thought believes the entire manifested reality to spring from this consciousness, these three curves therefore represent the entire physical phenomenon.

The dot signifies the fourth state of consciousness, known in Sanskrit as turiya. In this state the consciousness looks neither outwards nor inwards, nor the two together. It signifies the coming to rest of all differentiated, relative existence This utterly quiet, peaceful and blissful state is the ultimate aim of all spiritual activity. This Absolute (non-relative) state illuminates the other three states.

Finally, the semi circle symbolizes maya and separates the dot from the other three curves. Thus it is the illusion of maya that prevents us from the realization of this highest state of bliss. The semi circle is open at the top, and does not touch the dot. This means that this highest state is not affected by maya. Maya only affects the manifested phenomenon. This effect is that of preventing the seeker from reaching his ultimate goal, the realization of the One, all-pervading, unmanifest, Absolute principle. In this manner, the form of OM

represents both the unmanifest and the manifest, the noumenon and the phenomenon.

As a sacred sound also, the pronunciation of the three-syllabled AUM is open to a rich logical analysis.

The first alphabet A is regarded as the primal sound, independent of cultural contexts. It is produced at the back of the open mouth, and is therefore said to include, and to be included in, every other sound produced by the human vocal organs. Indeed A is the first letter of the Sanskrit alphabet.

The open mouth of A moves toward the closure of M. Between is U, formed of the openness of A but shaped by the closing lips. Here it must be recalled that as interpreted in relation to the three curves, the three syllables making up AUM are susceptible to the same metaphorical decipherment. The dream state (symbolized by U), lies between the waking state (A) and the state of deep sleep (M). Indeed a dream is but the compound of the consciousness of waking life shaped by the unconsciousness of sleep.

AUM thus also encompasses within itself the complete alphabet, since its utterance proceeds from the back of the mouth (A), travelling in between (U), and finally reaching the lips (M). Now all alphabets can be classified under various heads depending upon the area of the mouth from which they are uttered. The two ends between which the complete alphabet oscillates are the back of the mouth to the lips; both embraced in the simple act of uttering of AUM.

The last part of the sound AUM (the M) known as ma or makar, when pronounced makes the lips close. This is like locking the door to the outside world and instead reaching deep inside our own selves, in search for the Ultimate truth.

But over and above the threefold nature of OM as a sacred sound is the invisible fourth dimension which cannot be distinguished by our sense organs restricted as they are to material observations. This fourth state is the unutterable, soundless silence that follows the uttering of OM. A quieting down of all the differentiated manifestations, i.e. a peaceful-blissful and non-dual state. Indeed this is the state symbolized by the dot in the traditional iconography of AUM."

A deeper insight into this mystic symbol reveals that it is composed of three syllables combined into one, not like a physical mixture but more like a chemical combination. Indeed in Sanskrit the vowel 'o' is constitutionally a diphthong compound of a + u; hence OM is representatively written as AUM.

Fittingly, the symbol of AUM consists of three curves (curves 1, 2, and 3), one semicircle (curve 4), and a dot.

The large lower curve 1 symbolizes the waking state (jagrat), in this state the consciousness is turned outwards through the gates of the senses. The larger size signifies that this is the most common ('majority') state of the human consciousness.

The upper curve 2 denotes the state of deep sleep (sushupti) or the unconscious state. This is a state where the sleeper desires nothing nor beholds any dream.

The middle curve 3 (which lies between deep sleep and the waking state) signifies the dream state (swapna). In this state the consciousness of the individual is turned inwards, and the dreaming self beholds an enthralling view of the world behind the lids of the eyes.

These are the three states of an individual's consciousness, and since Indian mystic thought believes the entire manifested reality to spring from this consciousness, these three curves therefore represent the entire physical phenomenon.

The dot signifies the fourth state of consciousness, known in Sanskrit as turiya. In this state the consciousness looks neither outwards nor inwards, nor the two together. It signifies the coming to rest of all differentiated, relative existence This utterly quiet, peaceful and blissful state is the ultimate aim of all spiritual activity. This Absolute (non-relative) state illuminates the other three states.

Finally, the semi circle symbolizes maya and separates the dot from the other three curves. Thus it is the illusion of maya that prevents us from the realization of this highest state of bliss. The semi circle is open at the top, and does not touch the dot. This means that this highest state is not affected by maya. Maya only affects the manifested phenomenon. This effect is that of preventing the seeker from reaching his ultimate goal, the realization of the One, all-pervading, unmanifest, Absolute principle. In this manner, the form of OM

represents both the unmanifest and the manifest, the noumenon and the phenomenon.

As a sacred sound also, the pronunciation of the three-syllabled AUM is open to a rich logical analysis.

The first alphabet A is regarded as the primal sound, independent of cultural contexts. It is produced at the back of the open mouth, and is therefore said to include, and to be included in, every other sound produced by the human vocal organs. Indeed A is the first letter of the Sanskrit alphabet.

The open mouth of A moves toward the closure of M. Between is U, formed of the openness of A but shaped by the closing lips. Here it must be recalled that as interpreted in relation to the three curves, the three syllables making up AUM are susceptible to the same metaphorical decipherment. The dream state (symbolized by U), lies between the waking state (A) and the state of deep sleep (M). Indeed a dream is but the compound of the consciousness of waking life shaped by the unconsciousness of sleep.

AUM thus also encompasses within itself the complete alphabet, since its utterance proceeds from the back of the mouth (A), travelling in between (U), and finally reaching the lips (M). Now all alphabets can be classified under various heads depending upon the area of the mouth from which they are uttered. The two ends between which the complete alphabet oscillates are the back of the mouth to the lips; both embraced in the simple act of uttering of AUM.

The last part of the sound AUM (the M) known as ma or makar, when pronounced makes the lips close. This is like locking the door to the outside world and instead reaching deep inside our own selves, in search for the Ultimate truth.

But over and above the threefold nature of OM as a sacred sound is the invisible fourth dimension which cannot be distinguished by our sense organs restricted as they are to material observations. This fourth state is the unutterable, soundless silence that follows the uttering of OM. A quieting down of all the differentiated manifestations, i.e. a peaceful-blissful and non-dual state. Indeed this is the state symbolized by the dot in the traditional iconography of AUM."

Wheel of Dharma

Prayer Beads

I emailed a friend's relative who is a Buddhist, Jonathon Ashton, to find out about Buddhism on a personal level:

1. How long have you been a Buddhist? You could say: on and off since 1993. Often people would say "I'm a Buddhist" when they've decided to "go for refuge" and maybe even done a formal ceremony to acknowledge that. (I'd personally say,though, "How far are you really going for refuge?") In 1993, I got to the point of saying, "Yes, I am going for refuge now I believe from experience that Buddhism must be true. Even though I haven't really experienced its depths, I can see they should be there and that there should be a path to them and I'll try and follow it. However, I personally think of myself of a Buddhist to the extent that I'm practicing - it's not like Christianity where you can sign up and that's it, you're either following/trying to follow the path, or act in accordance with what you discover as the true nature of reality, or you aren't doing any of that. And when you're doing so, you're still only doing it to the extent that you're doing it. So, for me, the question would be "How far am I a Buddhist - at the moment and in general?" That's the kind of way someone from the Triratna Buddhist Community might see "being a Buddhist", btw. Ringu Tulku Rinpoche says that, given that most of Buddhism isn't accessible to people at the start, the only thing you really need to believe to become a Buddhist is that you can change. He's one of my main teachers, but I don't personally find that a complete enough answer.

2. What type/ kind /division of Buddhism are you involved in? I'm basically a Tibetan Buddhist. The practices I do, the teachers I go and see and by and large my "religious" thoughts about life and dealing with it are Tibetan Buddhist. However, I've done some practice in the Therevaddin, the Triratna Buddhist Community and Zen traditions, as well. (I know various other people who've done the same.) A word on the differences. Enlightenment is enlightenment, the basic nature of things is the basic nature of things. (Perhaps not everyone would 100% agree on this, but it would be a commonly held viewpoint.) However, the ordinary human mind is hard to work with and there are many different approaches and views about doing so. There are many different things that are thought helpful in "waking up". So, one can have a difference of opinion about what's most useful, or an evolution of techniques over time. This is the kind of sense in which the schools of Buddhism are different. My teacher Lama Yeshe Rinpoche has put it this way: 'Some people make great pasta and pasta is great. Some people make great porridge and porridge is great. However, you wouldn't want to be making pasta and porridge as the same dish. You have to choose which you are going to make and learn from someone who knows how to make it." Occasionally you'll meet Buddhist fundamentalists regarding their way of doing things - just as you'll meet teachers who passionately regard their approach as the most effective. However, the respect for other schools that Lama RInpoche shows above is pretty common in the West. Another point about different schools and lineages. Buddhist teachings are passed in a chain from teacher to student. So again, there are lots of different chains of transmission. By the way, the most common language used in the West is "school" of Buddhism, which I think is helpful. In the West there is a commonly shared view that there shouldn't be too many beliefs in Buddhism (as evidenced by the great popularity of a book titled "Buddhism Without beliefs"!) - it's about learning how things are, principally in the West from experience, though logical analysis can be used. It's then about what to do about how things are, again from experience. In countries where Buddhists grow up in a widely shared popular religious culture that is almost in their bones, it tends to operate differently (I suspect they might get quicker results with their students that way).

3. Why did you become a Buddhist? What got you into Buddhism? Firstly, aged 16 I stepped back from Christianity because I thought it would be hard to view the issue of religion and values objectively while I was practicing. (This is not to nay say Christianity. I actually now have a very high opinion of serious, practicing Christians such as my Mum as a result of my Buddhist practice. I have read some very inspiring interviews with leading Christians, esp. Christian mystics and enjoyed working in an administrative role at The Salvation Army.) Secondly, I suffered quite badly from depression on and off in my first year at university, drinking heavily, having problems with suicidal thoughts, etc - and then again later, after I left. (I've never told Roxanne that, btw, but you are welcome to mention it if you want, I'm not embarrassed.) Buddhism did three things that helped with my mental health: * The practices helped me to handle, or with other practices to overcome, my depression (which has been good for my faith - meaning my ability to trust Buddhism and put some weight on it, if you like). In particular, I did a lot of practice to generate more loving kindness towards myself and all other beings. It's not possible to simultaneously be angry and destructive and to be loving. So, as you can imagine that was one thing that helped a lot in uprooting the seeds of the depression. * The depression was aggravated by a nihilistic sense that there was no reliable, final value in the world. I'd been a very postmodern young man and had found the idea that everything I believed was dependent on my own history cultural background to be very threatening to my foundations for believing there's a meaningful reason to do good and be good, rather than it just being something that people do, maybe out of convenience or misunderstanding. My experience as a Buddhist gave me an anchor and (mixing metaphors) a compass for my life as a would-be good person. Even when, to my mind, I'm not a Buddhist in the sense of doing lots of meditation or something, I can now still be doing good in the world for an unchallengeable reason - and that's of great value to me. * Buddhism also made my depression useful. I could actively incorporate it into my practice (as a way into empathy with others in the same situation) and I could become a better person through it. Having a grasp of depression, anxiety, low self worth or despair has since become very useful: I've worked for a number of charities and had various mentally ill friends where it helped. My practice has helped that been a gateway to being able to do that without my memories and traces of those feelings being so much threatening things that I had to avoid. When the possibility first started to become real of being able to transcend and include depression as part of a meaningful life, through my practice, it was very beautiful and wonderful and extremely good for my faith! Thirdly, I was very Green at the time and Buddhism was a good philosophical fit with my strong interest in holistic worldviews and systems theory. (I can go into that if you want, but it might be a bit abstruse!) Buddhism fits well at a gut level with Postmodern sensibilities, too - though the language hasn't fully caught up, yet. (I can go into academic attempts to do so, if you are at all interested.) > 4. Do you attend any places of worship? How often? What is involved in these visits? > Right now, no. I'm not practicing very much and have been avoiding my local temple out of embarrassment! However, since 1992 I'd generally have gone to a Buddhist group at least once a week. There, a typical session of each school in the West that I've attended would be composed as follows: a. Tibetan Buddhism Either - Some silent meditation - either guided by the teacher or using your own practice. Sometimes the silent practice might be composed or interspersed with period of walking meditation. There will always be a short prayer at the start and the end, to help develop the best motivation for the meditation and so that you dedicate the benefit of it in a useful way, too. OR - a talk - which is usually didactic in approach. Some teachers tack a bit of meditation onto the front of the talk. Again, initial and final prayers would be the norm. OR - a "puja" such as "Chenrezig", "Amitabha", "Tara" (look "puja" up online) - once a month with tsok (offerings). This is the very colourful end of Tibetan Buddhism and the kind of practices that aren't (or often aren't) in the other traditions. People generally hang out and chat a bit either before or afterwards. Occasionally this is actively encouraged through a break in the middle, but not generally. b. FWBO Two sessions with a tea break in the middle. 1. Meditation, which is usually silent and may be guided or not 2. Either * More meditation * Or a teaching - which is generally more discursive and less didactic than in Tibetan Buddhism generally is * Or occasionally a "puja" (look it up) c. Zen I haven't practiced this so much, but it has been: Two sessions with a tea break in the middle. Whether this is a standard thing I don't know, it's just been my experience. 1. Meditation, which is silent and may be guided or not 2. Either * More meditation * Or a teaching - which is generally more didactic d. Therevaddin Buddhism Either - Some silent meditation - either guided by the teacher or using your own practice. Sometimes the silent practice might be composed or interspersed with period of walking meditation. There will always be a short prayer at the start and the end, to help develop the best motivation for the meditation and so that you dedicate the benefit of it in a useful way, too. Or (in the Forest Sangha tradition): Silent meditation. Prayers at the beginning to help develop an appropriate frame of mind would be the norm. Plus a talk, if there is a senior monk present - which is usually didactic in approach. . Plus generally maybe 10 or 20 minutes of traditional prayers People generally hang out and chat a bit either before or afterwards. Note: the range of meditation practices used in the different schools is maybe the single biggest difference between them. 5. What would it take (attitude / lifestyle) to become a Buddhist? See Q.1. and Q.7 Another important issue is not to take so much regarding how things are for granted. The assumptions we consciously and subconsciously make are an important problem that Buddhism seeks to overcome and an important challenge to effective practice. 6. Why would you recommend about the Buddhist lifestyle? The Dalai Lama said "My religion is kindness" and I do believe that's the whole point of doing it. Buddhism is about training the mind and practicing virtue well. One should do the things that are part of it that work for the individual. You have sometimes to treat yourself as an experiment - trying things out for a while to see if they do genuinely help in your own case. However, it's supposed to be about what you find works. If you aren't doing much that is clearly Buddhist you'd have to ask yourself "Am I really a Buddhist or am I just kidding myself?" However, after accepting that, for me personally, "the Buddhist lifestyle" is what makes you a better person. People today are very outwardly focused - except in exceptional circumstances, such as when they try and grapple with something like a major emotional upheaval. However, when it comes to why we choose to do things and how we go about them, it is hugely important where we actually come from and how we perceive, including emotionally perceive - things. To take an extreme example: to me, a lot of very selfish people, or very blinkered and materially driven people, are completely wasting much of their whole lives - and they may go through their whole life barely noticing that how they spend their time is not just bad but even completely irrelevant and meaningless. They couldn't comprehend that that might be the case because they are locked into it at a deep level and don't even realize that they have no freedom. You can see that from the Big Mind sessions. However, Elizabeth Kubler-Ross, the great figure in the hospice movement, observed that even very successful people, when they are dying, usually have no interest in their achievements. Their preoccupations about their lives are more "Have I loved?" and "Have I been loved?" In the face of impermanence, everything else starts to fall away. (Btw - my experience is that if you want to think deeply about death and what is of value in the face of it, I recommend you do so only in small doses and when relaxed.) At the moment I'm living a pretty worldly life, with lots of distractions with very little point. If there really is meaning to life, then all I'm doing is getting older - and even going backwards in some respects terms of spiritual progress. In a sense, that's a monumental waste of time, which I do find troubling. The spiritual life is sometimes hard (my main teachers wouldn't want it to be hard most of the time) but done properly I've almost always found it at least interesting and fulfilling. Paradoxically, even the boredom that comes with sitting for long hours on retreat becomes interesting! 7. How different is a Buddhist lifestyle to a none-religious lifestyle? (If you've known both, of course) Firstly, see Q1. A fairly serious Buddhist practitioner living in the West might well gradually build up to doing at least one session of meditation a day, which often might be between 45 minutes and a couple of hours a day depending on factors such as the tradition and their teacher's view. They may well go on retreat once or a number of times a year. They will probably go to a Buddhist Centre of some kind once a week. They may well have take various training commitments that help to live well - such as not to tell lies. Most likely it will impact on the other life choices they make - for example, practitioners tend to lead lives that seem socially useful. They are usually more generous as individuals (something that would be encouraged). Most choose to be vegetarians. This is a key difference between most Christians and most genuinely pretty committed Buddhists, for example - when you start trying to change your mind and your heart to become a better person, a common experience is to find that it's possible but requires a lot more time commitment than expected. The art is not to let it become oppressive! If you're "a better person" then of course that is time consuming but it is oppressive, you're very likely doing something in some sense wrong (and wasting a lot of time in just generating suffering and a fixed mind!) Kindness to oneself and others gradually comes to be seen as simply commonsense. I feel one should make commitments from a state of wealth - that actually,you have precious things you value and you are much better off not messing yourself around because you feel better and everything feels more meaningful. Take generosity. Being generous can often seem like a burden in the West - something you do out of or obligation, maybe. If you find you can do the Big Mind process on your own, try being the voice of generosity. Trungpa Rinpoche said "Generosity is self-existing openness, complete openness". You'll find that there's nothing constricted or oppressive about being the voice of generosity. Loving kindness is usually a warm, grounded, open and commonsensical experience and generosity is close to that. That said, as a practitioner one is sometimes put in positions where one may be exposed to the worst of oneself within the training and one has to grow by meeting it with love, wisdom and (in a sense) acceptance. That can be horrible at the time, however you only do it according to your skills and sense that you can do it - and it isn't necessarily horrible, sometimes it can be utterly amazing. However, you do it only because it is an opportunity to grow, not out of religious faith, duty or some kind of wierd masochism. A few points to balance the emphasis on the demands on time, above. Firstly, many teachers have said to me that ten minutes of meditation a day is better than nothing. Also,I have heard a few very senior teachers recommend particular practices as particularly well suited to and transformative for people living packed, busy lives. Also, even though I'm not doing much right now, I'm still in various ways a very different and better person as a result of my previous efforts. 8. Are you required to wear anything specific for your practices? Why? Personally,not really. It's usually key to try to relax. So, less restrictive garments are generally recommended. Monks and priests and in some traditions sometimes people on retreat do have particular clothing. I don't know why, really. 9. Are there any important pilgrimages specific to Buddhism? Do you have any personal pilgrimages? I've never done any, so I can't comment. Some people have done them and found them very useful. 10. And finally, anything else you'd like to tell me! Thubten Chodron did a very clear book, that I could annotate with notes about how the other traditions differ and send you.

He also sent me a few videos on Buddhism:

Links to Big Mind process The Big Mind Process is is not classical Buddhism. It doesn't exist in any of the ancient, mainstream traditions and you would need to be a little careful where you might cite it in an essay, if you did. However, it was developed and has been tested by Zen practitioners with excellent credentials and it does gives little glimpses of transcendent experience, which mean you can better answer many of your own questions about Buddhism! I suggest you try a couple of videos and have a go. I personally stop such videos at appropriate points and try and speak as the voices (e.g., you can say out loud "As seeking/non-seeking mind, I..." and speak about what you observe as that voice. Fake it 'til you make it, as Genpo Roshi says!) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JYjknUXy6hM This is a super-short one, which will take you ten mins - maybe 20 if you start and stop the video a lot. It's not a bad starting point, if you can get it. Note: the states that you access might only be a small aspect of the enlightened mind, but it does help a bit. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IkNrvs6ay0g This is a much longer one, going into, for example, the nature of compassion a bit more. Important note: the sections about worldly mind states such as "The Gatekeeper" are not Buddhism in the way that it would normally be understood. They're more like therapy or Western psychology. They do happen to be very useful for facilitating the Big Mind Process, in the sense of touching the transcendent states, though. The sections that involve integrating the mundane and the Big Mind-type states are also very useful for appreciating what it's really like to be successful spiritual practitioner. http://www.meditationplex.com/big-mind-meditation/big-mind-meditationat-the-buddhist-geeks-conference/ Also a long one!

The Conception of the Buddha:

the Chinese painting of the same scene. One more point that attracts our attention is that at this decisive moment of conception Maya is always shown alone on her couch; her husband is always absent. This restraint can be attributed to the religious belief of the time that everything having to do with the birth of the Buddha be physically and morally pure. This preoccupation with moral purity is carried over to the second act, the birth of the Buddha."

the Chinese painting of the same scene. One more point that attracts our attention is that at this decisive moment of conception Maya is always shown alone on her couch; her husband is always absent. This restraint can be attributed to the religious belief of the time that everything having to do with the birth of the Buddha be physically and morally pure. This preoccupation with moral purity is carried over to the second act, the birth of the Buddha."